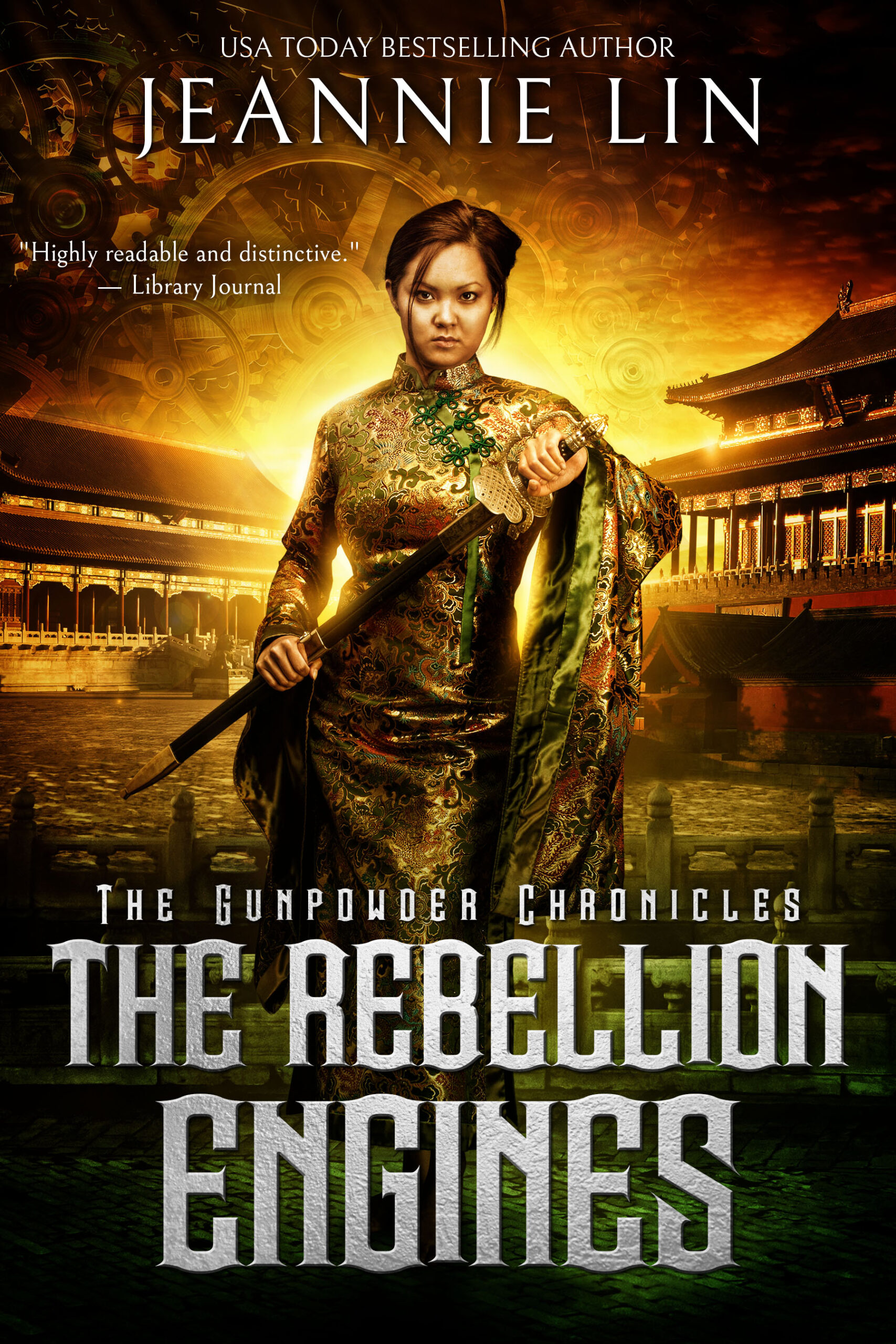

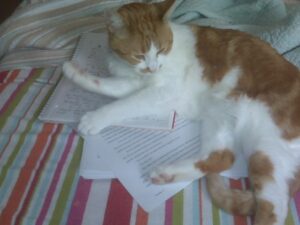

Before we get down to Little Sis’ critiquing prowess: Over this last week, I picked up some additional writing assistants:

Baby Peregrine likes to do his work early in the morning. Very early in the morning.

Ollie cat sits on my manuscript for a while before getting back to me

In addition to my new companions, I also got a chance to interview Sis about her reading process. Sis has killer instincts and I would pay for her feedback, but since we’re blood relatives, she seems to be willing to help me out of love and the occasional babysitting session.

To give you an idea of how clueless I was, I actually remember asking this question before I started seriously writing for publication: I asked Sis if it was possible to really learn how to improve writing. Don’t you just have to write and improve with practice? Her answer was that you can definitely study the craft of writing and that her writing had noticeably improved from the work in her program.

Huh. Writing as craft versus art. A light bulb moment for me, just to show you how helpless I’d be without Sis, who is my Secret Writing Weapon #1.

Sis is the one who taught me how to critique, but I realized that I usually go through the process instinctively, just modeling myself after the sorts of comments I’ve gotten from her many a time. I’ve always been fascinated that she actually took a class in her MFA program where the professor taught them how to critique. In her words, they would turn in one page writeups and receive feedback on whether their critique was good enough. How cool is that?

This professor will henceforth be referred to by the nickname Winky (don’t ask) for anonymity’s sake. Professor Winky was intent on teaching writers how to read critically and to give feedback that was usable–or as we say in the corporate world: actionable. He also believed that learning how to critique and “read like a writer” was essential to, well, becoming a better writer.

I’ve often said that my sister gives me feedback that elevates the manuscript. She tells me what the manuscript can become rather than pinpointing minor bugs. It helps me take what’s there and make it better. Often her comments will help me turn a whole scene or a whole section on its tail for the better. The feedback is deep, on point, sometimes requiring major rework on my part–but amazingly keeps to my intent for the manuscript.

I often feel that feedback that’s doing bug fixes really can’t take me anywhere beyond the frame I’ve set up. My manuscript doesn’t get better, it just gets spit shined a little. But when my Little Sis is done, I know how to break it out of its mold and make it bigger and better. (This is what my editor does as well, which has led me to respect Little Sis even more)

Professor Winky had a system for developing strong critiquers and my sister left her MFA program with those secrets in hand. It turns out the system revolved around one key question that I think we often overlook when giving feedback:

What is the author trying to accomplish?

Without this one guiding question, feedback is often piecemeal, spurious, disjointed — LAZY. Professor Winky was out to eradicate lazy critique just as much as he was out to eradicate lazy writing.

We had to do this in interview form since Little Sis had a bouncing baby in her arms, so here it is. From the mouth of my secret weapon herself.

Jeannie: You talked about rules that Winky set out. What were they?

Little Sis: They were pretty basic. You had to answer the question “What is the author trying to do?” You then had to identify a couple of things the author did well to achieve that goal and then give a couple suggestions on what they could do to improve on that goal. Also you couldn’t use “you” at all or refer to the writer. It had to be “the writing” or “these pages” or “this paragraph in the manuscript”.

He never said don’t do line edits, but it was implicit because it wasn’t in the questions.

Jeannie: Tell me about the process Winky would use in his class.

Little Sis: Well, every week someone would be assigned to turn in their writing. Everyone else would read it and turn in a one page written critique with the questions above before the session. Winky would collect the papers so they couldn’t just read it out loud in class.

During the critique session, the author would listen to everyone’s comments and wasn’t allowed to speak so there was no explaining, “But I meant…”

After the class, Winky would read through the one page critiques and call you in during office hours to comment on what you did that was useful. But he would also point out things that weren’t useful.Like blanket comments like “What’s at stake?” That’s what lazy critiquers throw out when they have nothing else to say. It’s a dead comment to a writer because they’re left to guess what they’re supposed to change to address it. The critiquer should be able to describe why it’s important they know what’s at stake for that particular scene, why and where do they feel it’s lacking, and provide some suggestions for improving it.

Jeannie: Oh yeah, the one I hear all the time is “There’s not enough conflict in the scene.” Definitely a problem, but not very useful as a standalone comment.

Little Sis: Yes. What do you feel is missing that would contribute to the conflict? What sort of conflict needs to be there? What’s another one that Winky was really peeved about…Oh yeah, “Show, don’t tell.”

Jeannie: *snickers*

Little Sis: As a blanket statement, it doesn’t mean anything. We had a professor who sat us down and said you’ve all heard so much about “Show, don’t tell” that you’re afraid to write a sentence like “He was afraid” when sometimes, that works perfectly.

Jeannie: People have heard “show, don’t tell” so much that writers try to substitute some convoluted way of showing emotion that ends up being artificial and is STILL TELLING.

Little Sis: Rob (BIL) mentioned once how a group was doing a critique in a scene where a guy was changing a tire, but the group just got all caught up on the details around changing a tire and the discussion just veered off into that description instead of focusing on something that was helpful. I told him that the instructor should have stopped that thread. They didn’t ask themselves, “What is the author trying to accomplish?” Is he really trying to write a scene about the technical details of changing a tire? If not, then you can make a brief remark about how this detail threw you off, but the critique should focus around what the author was trying to do.

Jeannie: Can you describe your approach when you first get a manuscript to read?

Little Sis: I read it through once for first impressions. My second read through is when I give comments because I know where it’s going and what it’s trying to do.

Jeannie: Do you do any sort of assessment for the level of where the manuscript is at?

Little Sis: That’s what the first read is for. If the manuscript is almost there, the next read will be for line edits. You don’t want to fix and change things if it’s really close.

Jeannie: (As I must have totally misconstrued my meaning there) The most common issue is people say there’s so much that needs fixing, they don’t know what to say.

Little Sis: If the manuscript is really rough, I’d start with character and motivation.

Even if the plot is ridiculous, ignore it for now. Once the characters are fixed, then they will pull the plot along. So next you can start talking plot and themes and sub-themes. Then after that, maybe pacing. That’s if you get a manuscript that’s very elementary and need to break it down. If you have someone pretty good, then you’ll address all of these at once according to what they’re trying to accomplish.

Jeannie: Line edits would be the last, last thing you do?

Little Sis: Yeah, cause that means it’s all fixed. The chapters are going to remain where they are. It just has to go from good to sparkly.

Jeannie: Where would you fit conflict under that? Character or plot or both?

Little Sis: Character. Maybe the author is allowed one or two freebie plot points to twist the story. If there’s more than that, the reader feels yanked around. Most of the plot should be that the characters made these decisions.

Jeannie: What do you think is the biggest shortcoming when people are critiquing?

Little Sis: They concentrate on grammar. Many people don’t realize that revising is not changing words. If the story is not working, you may have to change everything, take away maybe everything except for the central idea.

Jeannie: People hang on to words. They’re very hard to come up with.

Little Sis: I know. But the words are not written in stone. Use the delete key. 🙂

Also this happens a lot: when you give people comments and they argue or try to explain, “No, no…you don’t get it. I’m trying to do this…” They think that if people understood the reasoning, then the critique is no longer needed.

They don’t understand that 90% of the time, I know what they’re trying to do. I’m not giving the feedback because I don’t get what they want to do. I get it, but the writing didn’t accomplish its intended purpose. There’s a small percentage of the time when I didn’t get their original purpose and have to reassess and give different feedback.

And I’ve also learned (for some writers) that if they don’t give me a complete manuscript, I just say, “That’s good. Keep going.” (To not stop them in their tracks)

Rob: What sort of person are you a good reader for? Because you’re not for everyone.

(I stay silent as I sense some possible friction here. BIL and Sis met in the same MFA program.)

Little Sis: The person who thinks writing is a craft and a skill like any other. That there’s no mystique or talent about it and you can get better. Not a sensitive person.

I prefer someone who’s strong enough in their writing ability that they won’t take it personally. Or strong enough to consider feedback and decide whether or not it does help them. Strong enough to decide that my suggestion might not work, but maybe they can take it in another direction that’s even better than the original suggestion.

Back to Jeannie:

I think the coolest thing is we have conversations like this one all the time. Isn’t she smart? But she’s my Little Sis. Mine! And you can’t have her. Please let her know what you thought of this seemingly simple process that puts the onus onto the reader.