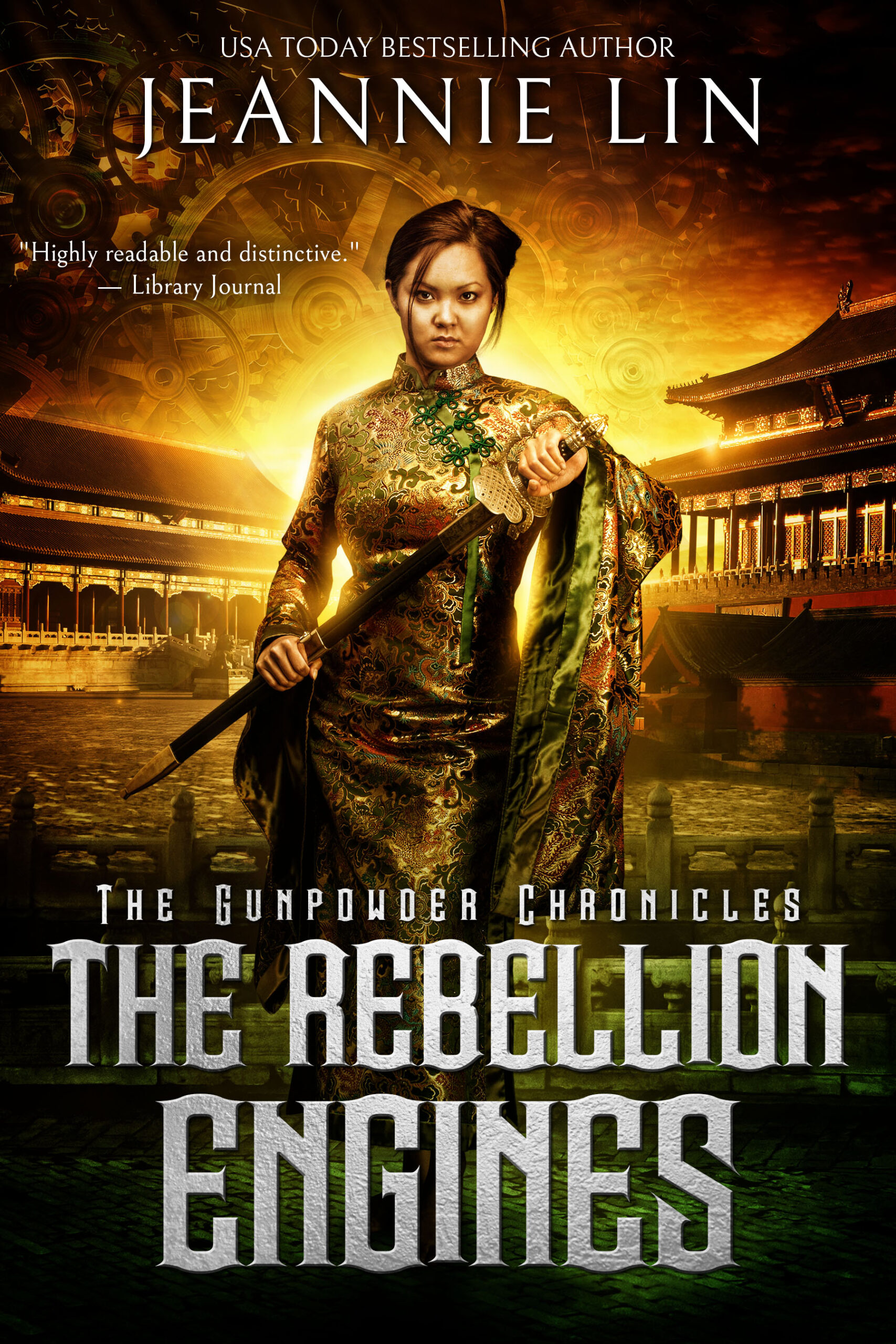

The Steampunk World of the Gunpowder Chronicles

Gunpowder Alchemy is an alternative history that takes place in China in the years after the first Opium War (1839–1842) and second Opium Wars (1856-1860).

In the timeline of Gunpowder, the Chinese empire were defeated by the British steam ships, just as they were in our timeline, and were forced to enter into an unequal trade agreement — allowing the British to trade in several of their key ports and push opium upon the people of China.

As I researched the Opium war period, I found the elements for conflict and intrigue already in place. Surprisingly little was altered in the historical record in order to allow the world of Gunpowder Alchemy to emerge.

In GA, the infamous Taiping rebels are referred to as the “Heavenly Kingdom Army” which is a translated description of what the Taiping army called itself.

Steampunk science and technology

The one big change to the imperial structure was the addition of the Ministry of Science to the traditional Six Ministries. The actual imperial exams didn’t include sections in mathematics or science — these topics being largely relegated to the areas of trade.

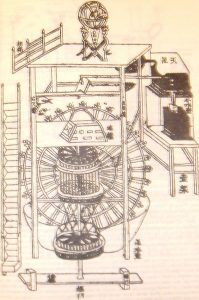

That’s not to say science didn’t flourish in ancient and imperial China. The Chinese invented paper and discovered gunpowder. They had developed water clocks and compasses and earthquake detection devices in ancient times. Yet Western history often presents China as being closed off and backward until it came into contact with Western technology.

Song Dynasty design of a hydraulic powered clock tower. (Image from Joseph Needham’s book Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering.)

That struck me as very odd–that there would be a sudden black hole in scientific development. From my research, it didn’t appear as if a gap truly existed. Nor were the Chinese as closed off to the West as often depicted. The fantastic instruments of the Beijing (aka Peking) Ancient Observatory is an early example of Western and Chinese collaboration when Jesuit Ferdinand Verbiest was granted charge of the observatory by the emperor in the 15th century and rebuilt some of the instruments.

The observatory was standing at the time of Gunpowder Alchemy and can still be seen today in modern Beijing.

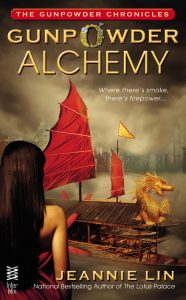

There were many forces driving the direction of scientific and technological development in China vs. in the West. The factors could have been as simple as the tendency to build with wood due to its abundance, leading to less skill in metalwork or perhaps less of a drive to develop stronger, faster ships due to the fact that China had dominated the seas for centuries already. The battened sails, famously seen on images of traditional Chinese junks as well as the cover of Gunpowder Alchemy–were adjustable and very effective at harnessing the wind, perhaps making the need for developing engines less prevalent.

There were many forces driving the direction of scientific and technological development in China vs. in the West. The factors could have been as simple as the tendency to build with wood due to its abundance, leading to less skill in metalwork or perhaps less of a drive to develop stronger, faster ships due to the fact that China had dominated the seas for centuries already. The battened sails, famously seen on images of traditional Chinese junks as well as the cover of Gunpowder Alchemy–were adjustable and very effective at harnessing the wind, perhaps making the need for developing engines less prevalent.

Or there were more complex human factors: the emphasis of scholarly learning on poetry and Confucianism at the expense of trade skills — science and mathematics. The hubris of the Emperor and the ruling class, believing that there was no way a tiny little island on the other side of the world could compete with China’s thousand years of perceived superior standing.

Or there were more complex human factors: the emphasis of scholarly learning on poetry and Confucianism at the expense of trade skills — science and mathematics. The hubris of the Emperor and the ruling class, believing that there was no way a tiny little island on the other side of the world could compete with China’s thousand years of perceived superior standing.

With this sort of cultural foundation in mind, both the East and the West possess steampunk-style technology in Gunpowder Alchemy, but where Western steampunk is often inspired by the likes of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells and the Victorian visions of technology, I wanted my Asian steampunk creations to be driven by the scientific mindset and visions that existed in the East.

Gunpowder fuel — There is an anecdote of an ancient Chinese astronomer using gunpowder rockets to propel himself into space. (You saw that episode of Mythbusters too, huh?). Much more practical was the use of gunpowder in cannons and fire-lances, very early precursors to firearms. The world of GA extrapolated those early inventions into the development of gunpowder combustion engines–a concept that was actually explored by the Dutch in the 1600s.

Heavy machinery — The Taiping rebels were believed to have originated in the Thistle Mountain area, many who were miners and skilled in excavation. This allowed them to take cities by tunneling under the walls and breaching them.

Heavy machinery — The Taiping rebels were believed to have originated in the Thistle Mountain area, many who were miners and skilled in excavation. This allowed them to take cities by tunneling under the walls and breaching them.

I took the liberty of supplying them with some heavy gunpowder-powered machinery, which Soling gets a brief glimpse of one of the machines in a junkyard, comparing it a beast or dragon:

The industrial workers of the south were thus equipped with more technology than the rest of the rural population in the region, giving them an advantage in their rebellion.

Acupuncture prosthetics — What would steampunk be without a few mechanical appendages? Given the longstanding practice of acupuncture in China, it made sense that this would be a method of connecting a mechanical prosthetic to nerve impulses for finer control.

Man-flying kite — Kite-making has a long tradition in China, of course, but I found an interesting reference in the Travels of Marco Polo which mentioned a kite that was large enough to fly a man in the air. Turns out this was something actually developed in China and I didn’t make it up at all.

Man-flying kite — Kite-making has a long tradition in China, of course, but I found an interesting reference in the Travels of Marco Polo which mentioned a kite that was large enough to fly a man in the air. Turns out this was something actually developed in China and I didn’t make it up at all.

Earthquake detection – Earthquakes were very important to Chinese emperors because they were a sign of ill-favor from heaven. So the Emperor had a stake in being able to predict in advance or at least know when an earthquake had occurred. GA features an ancient earthquake detector where a ball is dropped from a dragon’s mouth into a frog’s mouth below. The location of the ball drop indicated the direction of the quake and the Emperor would send riders out in that direction to check on things. Later in Gunpowder Alchemy, a more advanced earthquake detector was developed by Soling’s brother which had more in common with a modern day seismograph.

Historical Personalities in Gunpowder Alchemy

Crown Prince Yizhu – Is the actual crown prince, later known as the Xianfeng Emperor, who took the throne at the age of 19 right at the onset of the Taiping Rebellion as well as right between the two Opium Wars. Tough gig! Unfortunately, history doesn’t remember him kindly, though it is said that he excelled in literature and administration, which was why he was promoted to crown prince over his brothers. Gunpowder Alchemy’s Yizhu remains a mysterious character with his motivations not made completely clear. (Trivia: Even if you’ve never heard of Yizhu, you’ve probably heard of one of his wives. She’s most famously known as Dowager Empress Cixi, who ruled as regent after his death.)

Dowager Empress Cixi (Image: public domain)

Lady Su – The rebel leader is based on real-life Taiping rebel leader, Su Sanniang. Like her real-life counterpart, Lady Su’s husband was wrongfully killed. When the authorities couldn’t or wouldn’t do anything about it, she took revenge into her own hands and went after his murderer herself, recruiting her workmen to her cause. Her actions made her an outlaw and she took to the bandit life, acting as a female Robin Hood of sorts and attracting more followers, until joining up with the rebel army.

(Side note: I dare–no, I DOUBLE DOG dare anyone to tell me that I altered history to create such strong, independent Chinese women in Gunpowder Alchemy.)

Zuo Zongtang – In Gunpowder Alchemy, he appears as an administrator in the city of Changsha during the final seige. In real life, he was born near Changsha and there is some record of him acting as a minor official during the seige. Zuo goes on to become an important general in the Taiping Rebellion, ultimately helping to defeat the rebel army. Trivia: Another spelling of his last name is “Tso.” The popular dish “General Tso’s Chicken” is supposedly named in his honor, though it was unlikely he himself ever tasted anything resembling General Tso’s Chicken.

And now as I’m in the midst of writing the sequel, Clockwork Samurai (out sometime in 2015), I’m finding that Japanese culture and technological developments equally if not even MORE fascinating. I’ll certainly update this page once that project is done!

In the meantime, Gunpowder Alchemy is available now. If your curiosity has been piqued at all. 🙂