Gambled Away: A historical romance anthology releases this week featuring new novellas by superstars Molly O’Keefe, Rose Lerner, Joanna Bourne, Isabel Cooper and myself.

Gambled Away: A historical romance anthology releases this week featuring new novellas by superstars Molly O’Keefe, Rose Lerner, Joanna Bourne, Isabel Cooper and myself.

It’s pretty much a dream come true to be invited to this anthology along with authors I not only admire and respect, but ADORE.

As there was no room for an extensive author’s note in the collection, I did want to take the time to note a few super geeky background notes.

First, I don’t mean for any of this info as an explanation for the story. The story must stand alone! And if, while reading, a historical buff finds one of these anachronisms and it yanks them out of the story, then mea culpa. It was my fault that I didn’t execute and the story didn’t deliver.

This disclaimer is wholly due to my current annoyance with The Talking Dead which, as of late, comes on right after The Walking Dead to explain, apologize, promise, spin why what we just saw was the best storytelling ever!!…when it wasn’t. It so wasn’t.

Now on to the tidbits and trivia!

1. On Wei-wei:

Wei-wei is the character who I get the most fan mail for. As a historical heroine, Wei-wei is perhaps an uncommon woman for her time, but not an anachronistic one. The reason I love her is because I believe she existed a thousand years ago and that she exists today. She’s the straight A student who can do no wrong in her parents’ eyes, yet sneaks out of the house at night to meet up with her friends. (Not that I’m, uh, speaking from experience or anything. Hi Mom!)

She was always meant to be the lead in a third “Lotus Palace” book. The problem, however, was that I couldn’t ever find a way that any man could woo her, or a way that Wei-wei would allow herself to be wooed in the space of one book. This made her a very difficult romance heroine for me, so I was happy to have to chance to play with her story in “The Liar’s Dice” and see where she might lead.

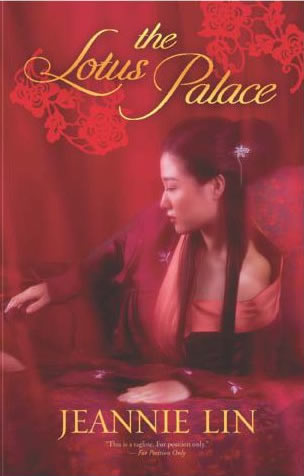

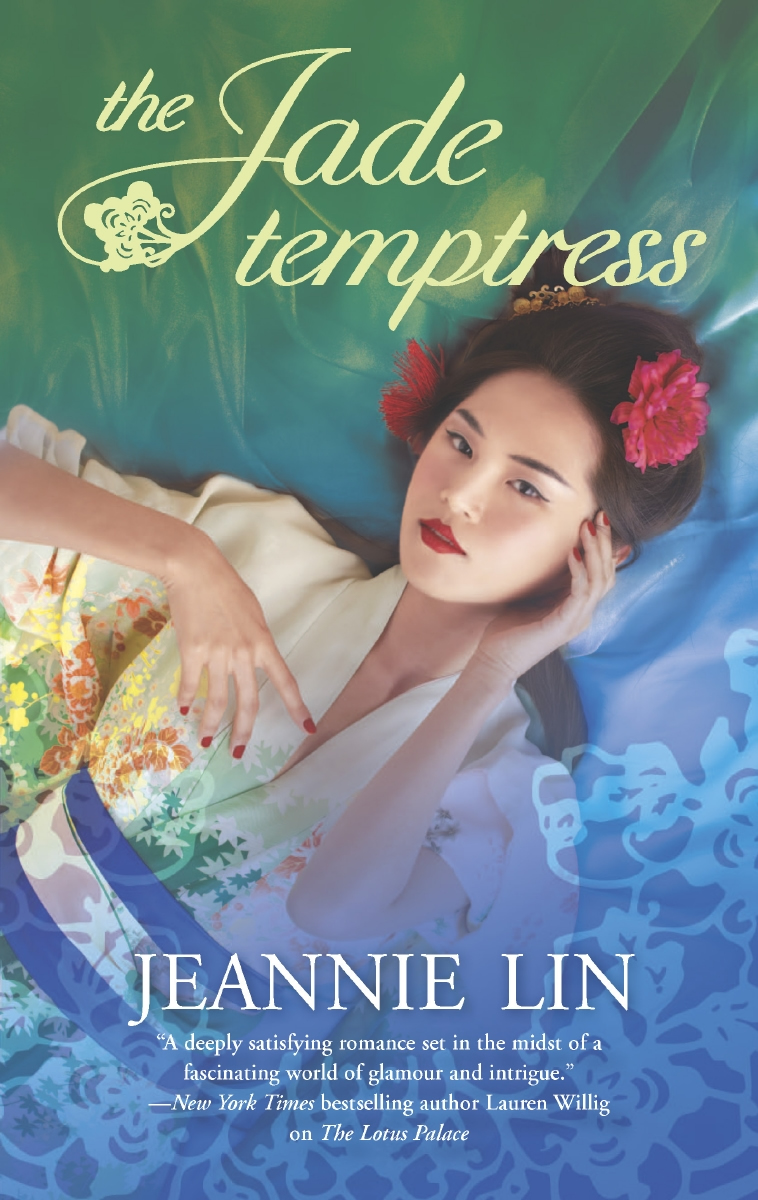

2. The plot is a continuation of several storylines first visited in The Lotus Palace and The Jade Temptress, though The Liar’s Dice can be read as a standalone.

3. Liar’s Dice is a popular bluffing game in China, usually involving drinking. Though there were certainly drinking games and most certainly bluffing games played in Tang Dynasty parlors, the actual liar’s dice game probably has a more contemporary origin–though I was unable to pin down the exact origins.

4. The original name of the novella was “The Precious Dice” which is a literal translation of sic bo (骰寶), a very popular game that does have ancient origins in China. This high-low dice game is the one that’s actually played in the course of the story.

From here the notes get super nerdy. Like, I can’t imagine anyone but the buffest of history buffs even remotely finding this interesting. (Though I find it all absolutely fascinating!)

5. The tragic love story that inspires Wei-wei is popularly known as The Butterfly Lovers and is set during the Eastern Jin Dynasty (265-420 AD). There are mentions of the folktale in the Late Tang Dynasty, such as in the Xuan Shi Zhi (Tales of Ghosts and Gods) by Zhang Du. Xuan Shi Zhi was written between 851-874 A.D. Even assuming that the folktale may have been known prior to the published work, I took some liberties by having the work be known well enough that Wei-wei has a copy of the story by 849 A.D.

6. On cross-dressing and general boundary pushing: Though not a reliable historical source, popular folk legends of the Tang Dynasty indicate that women had a “rebel spirit” and would dress in men’s clothing, climb walls, and ride horses. Whether or not this actually happened in the Tang Dynasty is not something I bother myself with too often. What’s more compelling is that there is a prevailing popular belief that Tang women did these things. I have said before that my Tang Dynasty is a romantic version of the Tang Dynasty. What is historically known is that princesses commanded armies, female politicians reached the highest level of government, and women played polo alongside men.

7. Female scholarship: I always found it interesting that books on proper conduct for women were written by female scholars, not by men. One of the Four Books for Women, The Analects for Women, was written by Tang Dynasty scholar Song Ruxian and her sister Song Ruozhao, who were both brought before the Emperor along with their three sisters. All five so impressed the Emperor with their knowledge that he recognized them as scholars, inviting them to literary events and giving them official administrative posts. Wei-wei was inspired by these women who were able to achieve respect through scholarship.