I loved reading about the alternative history behind Meljean Brook’s Iron Seas series on her website where she describes the real history of the Mongolian khagans or khans and their contact with the West via Marco Polo and then ties that in to the alternative history she created about the Golden Horde. So I thought it would be good to write up the alternative history of BUTTERFLY SWORDS and THE DRAGON AND THE PEARL.

My world isn’t as imagineered as a full on fantasy novel. In fact I was adamant in the fact that they are set in Tang Dynasty China. Not a fantasy world based on the Oriental trappings of China. I strive to try to be as authentic as possible in terms of culture, social climate, and political structure. I didn’t want to make up place names and customs and hide behind the fact that I made things up if something reads inauthentic. If it didn’t work, it’s because I didn’t sell it–not because it was meant to be fabricated anyway.

Of course wuxia, and really all similar chivalric tales, take place within a bit of a fantasy world. For the western equivalents, consider the Tales of Robin Hood or King Arthur. They’re a bit of historical fantasy. Historical romances are also really historical fantasies in the way authors have freedom to make up Dukes and Princes and Princesses. One of the reasons I feel so strongly that I’m truly in the right genre.

But one of the big leaps that I made that is not done too often in traditional historical romance is I altered the macro-history of my setting. Often authors will create imaginary kingdoms to satisfy the need to create wars and political conflict, but I had already decided this would not be a made up kingdom. So here’s the real history and my alternate history juxtaposed.

WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE REAL TANG DYNASTY AND JEANNIE LIN’S TANG DYNASTY?

In the real Tang Dynasty:

The rule of Emperor Xuanzong, named Li Longji, (712-756 A.D.) is often considered the pinnacle of the Tang Dynasty. Near the end of his reign however, the empire began to decline through many different factors including famine and several devastating military losses, costing Xuanzong several of the empire’s tributary nations. Throughout the dynasty, military warlords called jiedushi who were tasked with leading campaigns against neighboring kingdoms and maintaining order at the frontier had gained in power and influence. The jiedushi took over the military rule of their provinces, forming armies that were independent from the central imperial army. It was the combination of this military decentralization and the financial weakening of the central government that allowed the first strike in the beginning of the fall of the Golden Age.

The most popular telling has Emperor Xuanzong declining into decadence and extravagance in his elder years. He became smitten by one of his concubines, Lady Yang Yuhuan, who is more commonly known as Yang Guifei (Precious Consort Yang). Under her thrall, he ignored matters of state, appointed her relatives and other corrupt men to important governmental positions, and spent his days throwing lavish banquets for his consort. One of the men who gained the favor of the corrupt court was a warlord by the name of An Lushan, who was of Sogdian (ancient Persian empire) descent rather than pure “Chinese”. (During the Tang Dynasty, the population of the empire was a mix of ethnicities, much like the Roman Empire during its height.) An Lushan had gained prominence defending the northeastern border against the Khitans and between he and his sons, controlled several military districts and a sizeable army. One of the downfalls of the military system was that too many men were elevated to governorships from lowly field positions. As a result, the imperial government had to contend with and try to balance the demands of many powerful factions within its own borders.

In 755, An Lushan led the Anshi Rebellion against Xuanzong, forcing the Emperor to flee from the capital. During the tragic flight, the Emperor’s army refused to continue unless he executed his beloved Yang Guifei, blaming her and her inept cousin, Chancellor Yang Guozhong, for the downfall of the imperial government. The Emperor had Yang Guifei strangled and her body was buried by the roadside while the escort continued on to Chengdu in the South.

An Lushan took over control of the dual capitals of Chang’an and Luoyang and declared himself Emperor. Meanwhile, Xuanzong set up a separate court in the south, but he was a broken man. He recognized his son, Li Heng’s, ascension to the throne and took on the title of retired Emperor. The son mounted a campaign against An Lushan to try to recapture the capital and destroy the warlord’s forces, though it would take the reign of three Tang Emperors before the rebellion was crushed in 763 A.D.

The Tang Dynasty continues for over another century, finally ending in 907 A.D. though it never reaches the height of Xuanzong’s rule again.

In Jeannie Lin’s Tang Dynasty:

BUTTERFLY SWORDS and THE DRAGON AND THE PEARL take place during the period of the Anshi rebellion, though the alternative history changes the circumstances of the temporary fall of the Tang Emperors. Emperor Xuanzong is replaced by a fictional Emperor Li Ming, known as the August Emperor, who has died without leaving behind any direct male descendants.

Instead of An Lushan, a warlord named Shen An Liu has taken control during the unrest and Li Ming’s only daughter Miya has abdicated the throne and lives in exile. Emperor Shen and his sons control the largest military force in the empire, allowing them to maintain control of the central part of the kingdom, but his rule is constantly challenged by the other warlords, many who want to restore a Tang ruler to the throne.

The tragic figure of Yang Yuhuan was replaced by Precious Consort Ling Suyin, who survives the fall of Tang regime. Li Tao is a commoner who was given military command as jiedushi by the August Emperor.

In this timeline, Emperor Shen is seen as a usurper of low birth and mixed blood, though he does rule over the central government. A clear opposition government has yet to be established and the jiedushi are left to fight it out about who will control the empire.

It was a difficult decision to alter such pivotal events in the Tang Dynasty history to create this world. The intention was to be able to use pivotal figures such as Emperors and warlords and consorts and set their interactions during the tumultuous time that inspired me. I hope readers will realize that these stories are historical fantasy and not meant to be a historical reference.

For the upcoming tales that do not reference this alternative timeline, I’ve set the time period to the later part of the Tang Dynasty after 800 A.D. to differentiate them from these earlier tales.

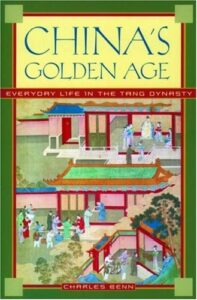

As I’ve heard from readers that these stories have been the first taste they got of the Tang Dynasty, I encourage any history geeks to seek out the true events. The following resources were the basis for much for much of my research:

- Benn, Charles (2002), China’s Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-517665-0

- Hucker, Charles O. (1995), China’s Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture, Stanford University Press, ISBN 0804723532

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2009), China’s Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 067403306X